External radiotherapy for oesophageal cancer

Radiotherapy uses high energy waves similar to x-rays to kill cancer cells.

External beam radiotherapy directs radiotherapy beams at the cancer from a machine. This is different to internal radiotherapy. Internal radiotherapy means giving radiotherapy to the cancer from inside the body.

This page is about external beam radiotherapy.

When do you have it?

For early stage oesophageal cancer, you might have radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy (chemoradiotherapy) before surgery. Or you may have chemoradiotherapy on its own as your main treatment.

You might have radiotherapy on its own to control symptoms of oesophageal cancer that has spread (advanced cancer).

You usually have treatment every day for a few weeks. Your doctor will tell you how long your treatment will last.

Where do you have it?

You have external radiotherapy in a hospital radiotherapy department. Some hospitals have rooms near the hospital you can stay in if you have a long way to travel. You go to the radiotherapy department from your ward if you’re already in hospital.

Planning radiotherapy

The radiotherapy team plan your external radiotherapy before you start treatment. This means working out the dose of radiotherapy you need and exactly where you need it.

Your planning appointment takes from 15 minutes to 2 hours.

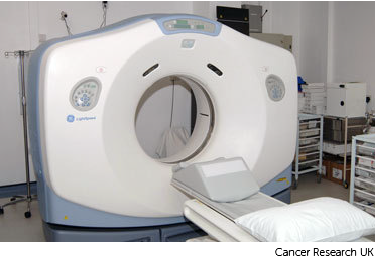

You usually have a planning CT scan in the radiotherapy department.

The scan shows the cancer and the area around it. You might have other types of scans or x-rays to help your treatment team plan your radiotherapy. The plan they create is just for you.

Your radiographers tell you what is going to happen. They help you into position on the scan couch. You might have a type of firm cushion called a vacbag to help you keep still.

The CT scanner couch is the same type of bed that you lie on for your treatment sessions. You need to lie very still. Tell your radiographers if you aren't comfortable.

Injection of dye

You might need an injection of contrast into a vein in your hand. This is a dye that helps body tissues show up more clearly on the scan.

Before you have the contrast, your radiographer asks you about any medical conditions or allergies. Some people are allergic to the contrast.

Having the scan

Once you are in position your radiographers put some markers on your skin. They move the couch up and through the scanner. They then leave the room and the scan starts.

The scan takes about 5 minutes. You won't feel anything. Your radiographers can see and hear you from the CT control area where they operate the scanner.

The radiographers make pin point sized tattoo marks on your skin. They use these marks to line you up into the same position every day. The tattoos make sure they treat exactly the same area for all of your treatments. They may also draw marks around the tattoos with a permanent ink pen, so that they are clear to see when the lights are low.

The radiotherapy staff tell you how to look after the markings. The pen marks might start to rub off in time, but the tattoos won’t. Tell your radiographer if that happens. Don't try to redraw them yourself.

Radiotherapy shell (mould)

If your cancer is higher up in your oesophagus, your treatment team might make a mould (shell) for you. This goes over your head and shoulders.

You wear it during the treatment sessions to keep you very still. The radiographers may also make marks on it. They use the marks to line up the radiotherapy machine for each treatment.

The process of making the shell can vary slightly between hospitals. It usually takes around 30 minutes.

A technician uses a special kind of plastic that they heat in warm water. This makes it soft and pliable. They put the plastic on to your face, neck and chest so that it moulds exactly. After a few minutes the plastic gets hard. The technician takes the shell off and it is ready to use.

You might have to wait a few days or up to 3 weeks before you start treatment.

During this time the physicists and your radiotherapy doctor (clinical oncologist) decide the final details of your radiotherapy plan. They make sure that the area of the cancer will receive a high dose and nearby areas receive a low dose. This reduces the side effects you might get during and after treatment.

Having radiotherapy

Radiotherapy machines are very big and could make you feel nervous when you see them for the first time. The machine might be fixed in one position. Or it might rotate around your body to give treatment from different directions. The machine doesn't touch you at any point.

Before your first treatment, your  will explain what you will see and hear. In some departments, the treatment rooms have docks for you to plug in music players. So, you can listen to your own music while you have treatment.

will explain what you will see and hear. In some departments, the treatment rooms have docks for you to plug in music players. So, you can listen to your own music while you have treatment.

Before your treatment

The radiographers help you to get into position on the treatment couch. They fit your mask if you need one to keep you still during the treatment session.

They line up the radiotherapy machine, using marks on the mask or on your skin.

You might need to raise your arms above your head.

Then the radiographers leave you alone in the room for a few minutes. This is so they aren't exposed to radiation.

Daniel (radiographer): Before your treatment starts your doctor will need to work out exactly where the treatment needs to go and also which parts need to be avoided by the treatment.

To have radiotherapy you lie in the same position as you did for your planning scans.

To stop you moving and to make sure your treatment is directed at the cancer you wear a custom mask over your face which is attached to the couch.

We line up the machine using marks on your mask and then leave the room. We control the machine from a separate room this is so we aren’t exposed to radiation.

Treatment takes a few minutes and you’ll be able to talk to us using an intercom. We can see you and hear you while you’re having treatment and we will check that you’re OK.

When your treatment starts you won’t feel anything. You may hear the machine as it moves around you giving the treatment from different angles.

Because we’re aiming to give the same treatment to the same part of the body every day the treatment process is exactly the same everyday so you shouldn’t really notice any difference.

You’ll see someone from the team caring for you once a week while you’re having treatment. They’ll ask how you are and ask about any side effects.

During the treatment

You need to lie very still. Your radiographers might take images (x-rays or scans) before your treatment to make sure that you're in the right position. The machine makes whirring and beeping sounds. You won’t feel anything when you have the treatment.

Your radiographers can see and hear you on a CCTV screen in the next room. They can talk to you over an intercom and might ask you to hold your breath or take shallow breaths at times. You can also talk to them through the intercom or raise your hand if you need to stop or if you're uncomfortable.

You won't be radioactive

This type of radiotherapy won't make you radioactive. It's safe to be around other people, including pregnant women and children.

Travelling to radiotherapy appointments

You might have to travel a long way each day for your radiotherapy. This depends on where your nearest cancer centre is. This can make you very tired, especially if you have side effects from the treatment.

You can ask the  for an appointment time to suit you. They will do their best, but some departments might be very busy. Some radiotherapy departments are open from 7 am till 9 pm.

for an appointment time to suit you. They will do their best, but some departments might be very busy. Some radiotherapy departments are open from 7 am till 9 pm.

Car parking can be difficult at hospitals. Ask the radiotherapy staff if you are able to get free parking or discounted parking. They may be able to give you tips on free places to park nearby.

Hospital transport may be available if you have no other way to get to the hospital. But it might not always be at convenient times. It is usually for people who struggle to use public transport or have any other illnesses or disabilities. You might need to arrange hospital transport yourself.

Some people are able to claim back a refund for healthcare travel costs. This is based on the type of appointment and whether you claim certain benefits. Ask the radiotherapy staff for more information about this and hospital transport.

Some hospitals have their own drivers and local charities might offer hospital transport. So do ask if any help is available in your area.

Side effects of treatment

Radiotherapy to the oesophagus can make you tired and make your mouth and throat sore. You may also have difficulty eating.